Transplanting go packages for fun and profit

A while back I read coders at work, which is a book of interviews with some great computer scientists who earned their stripes, the questions just as thoughtful as the answers. For one thing, it re-ignited my interest in functional programming, for another I got interested in literate programming but most of all, it struck me how common of a recommendation it was to read other people’s code as a means to become a better programmer. (It also has a good section of Brad Fitzpatrick describing his dislike for programming languages, and dreaming about his ideal language. This must have been shortly before Go came about and he became a maintainer.)

I hadn’t been doing a good job reading/studying other code out of fear that inferior patterns/style would rub off on me. But I soon realized that was an irrational, perhaps slightly absurd excuse. So I made the decision to change. Contrary to my presumption I found that by reading code that looks bad you can challenge and re-evaluate your mindset and get out with a more nuanced understanding and awareness of the pros and cons of various approaches.

I also realized if code is proving too hard to get into or is of too low quality, you can switch to another code base with negligible effort and end up spending almost all of your time reading code that is worthwhile and has plenty of learnings to offer. There is a lot of high quality Go code, easy to find through sites like GitHub or Golang weekly, just follow your interests and pick a project to start reading.

Contrary to my presumption I found that by reading code that looks bad you can challenge and re-evaluate your mindset

It gets really interesting though once you find bodies of code that are not only a nice learning resource, but can be transplanted into your code with minimal work to solve a problem you’re having, but in a different context then the author of the code originally designed it for. Components often grow and mature in the context of an application without being promoted as reusable libraries, but you can often use them as if they were. I would like to share 2 such success cases below.

Nsq’s diskqueue code

I’ve always had an interest in code that manages the same binary data both in memory and on a block device. Think filesystems, databases, etc. There’s some interesting concerns like robustness in light of failures combined with optimizing for performance (infrequent syncs to disk, maintaining the hot subset of data in memory, etc), combined with optimizing for various access patterns, this can be a daunting topic to get into.

Luckily there’s a use case that I see all the time in my domain (telemetry systems) and that covers just enough of the problems to be interesting and fun, but not enough to be overwhelming. And that is: for each step in a monitoring data pipeline, you want to be able to buffer data if the endpoint goes down, in memory and to disk if the amount of data gets too much. Especially to disk if you’re also concerned with your software crashing or the machine power cycling.

This is such a common problem that applies to all metrics agents, relays, etc that I was longing for a library that just takes care of spooling data to disk for you without really affecting much of the rest of your software. All it needs to do is sequentially write pieces of data to disk and have a sequential reader catching up and read newer data as it finishes processing the older.

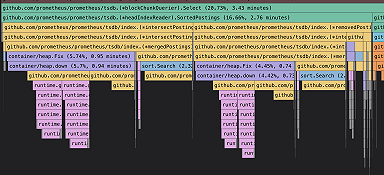

NSQ is a messaging platform from bitly, and it has diskqueue code that does exactly that. And it does so oh so elegantly. I had previously found a beautiful pattern in bitly’s go code that I blogged about and again I found a nice and elegant design that builds further on this pattern, with concurrent access to data protected via a single instance of a for loop running a select block which assures only one piece of code can make changes to data at the same time (see bottom of the file), not unlike ioloops in other languages. And method calls such as Put() provide a clean external interface, though their implementation simply hooks into the internal select loop that runs the code that does the bulk of the work. Genius.

func (d *diskQueue) Put(data []byte) error {

// some details

d.writeChan <- data

return <-d.writeResponseChan

}In addition the package came with extensive tests and benchmarks out of the box.

After finding and familiarizing myself with this diskqueue code about a year ago I had an easy time introducing disk spooling to Carbon-relay-ng, by transplanting the code into it. The only change I had to make was capitalizing the Diskqueue type to export it outside of the package. It has proven a great fit, enabling a critical feature through little work of transplanting mature, battle-tested code into a context that original authors probably never thought of.

The authors… rightfully shot down a PR of mine"

Note also how the data unit here is the []byte, the queue does not deal with the higher level nsq.Message (!). The authors had the foresight of keeping this generic, enabling code reuse and rightfully shot down a PR of mine that had a side effect of making the queue aware of the Message type. In NSQ you’ll find thoughtful and deliberate api design and pretty sound code all around. Also, they went pretty far in detailing some lessons learned and providing concrete advice, a very interesting read, especially around managing goroutines & synchronizing their exits, and performance optimizations. At Raintank, we had a need for a messaging solution for metrics so we will so be rolling out NSQ as part of the raintank stack. This is an interesting case where my past experience with the NSQ code and ideas helped to adopt the full solution.

Bosun expression package

I’m a fan of the bosun alerting system which came out of Stack Exchange. It’s a full-featured alerting system that solves a few problems like no other tool I’ve seen does (see my linked post), and timeseries data storage aside, comes with basically everything built in to the one program. I’ve used it with success. However, for litmus I needed an alerting handler that integrated well into the Grafana backend. I needed the ability to do arbitrarily complex computations. Graphite’s api only takes you so far. We also needed (desired) reduction functions, boolean logic, etc. This is where bosun’s expression language is really strong. I found the expression package quite interesting, they basically built their own DSL for metrics processing. so it deals with expression parsing, constructing AST’s, executing them, dealing with types (potentially mixed types in the same expression), etc.

But bosun also has incident management, contacts, escalations, etc. Stuff that we either already had in place, or didn’t want to worry about just yet. So we could run bosun standalone and talk to it as a service via its API which I found too loosely coupled and risky, hook all its code into our binary at once - which seemed overkill - or the strategy I chose: gradually familiarize ourself and adopt pieces of Bosun on a case by case basis, making sure there’s a tight fit and without ever building up so much technical debt that it would become a pain to move away from the transplanted code if it becomes clear it’s not/no longer well suited. For the foreseeable future we only need one piece, the expression package. Potentially ultimately we’ll adopt the entire thing, but without the upfront commitment and investment.

So practically, our code now simply has one line where we create a bosun expression object from a string, and another where we ask bosun to execute the expression for us, which takes care of parsing the expression, querying for the data, evaluating and processing the results and distilling everything down into a final result. We get all the language features (reduction functions, boolean logic, nested expressions, …) for free.

This transplantation was again probably not something the bosun authors expected, but for us it was tremendously liberating. We got a lot of power for free. The only thing I had to do was spend some time reading code, and learning in the process. And I knew the code was well tested so we had zero issues using it.

“This transplantation was again probably not something the bosun authors expected, but for us it was tremendously liberating."

Much akin to the NSQ example above, there was another reason the transplantation went so smoothly: the expression package is not tangled into other stuff. It just needs a string expression and a graphite instance. To be precise, any struct instance that satisfies the graphiteContext interface that is handily defined in the bosun code. While the bosun design aims to make its various clients (graphite, opentsdb, …) applicable for other projects, it also happens to let us do opposite: reuse some of its core code - the expression package - and pass in a custom graphite Context, such as our implementation which has extensive instrumentation. This lets us use the bosun expression package as a “black box” and still inject our own custom logic into the part that queries data from graphite. Of course, once we want to change the logic of anything else in the black box, we will need come up with something else, perhaps fork the package, but it doesn’t seem like we’ll need that any time soon.

Conclusion

If you want to become a better programmer I highly recommend you go read some code. There’s plenty of good code out there. Pick something that deals with a topic that is of interest to you and looks mature. You typically won’t know if code is good before you start reading but you’ll find out really fast, and you might be pleasantly surprised, as was I, several times. You will learn a bunch, possibly pretty fast. However, don’t go for the most advanced, complex code straight away. Pick projects and topics that are out of your comfort zone and do things that are new to you, but nothing too crazy. Once you truly grok those, proceed to other, possibly more advanced stuff.

Often you’ll read reusable libraries that are built to be reused, or you might find ways to transplant smaller portions of code into your own projects. Either way is a great way to tinker and learn, and solve real problems. Just make sure the code actually fits in so you don’t end up with the software version of Frankenstein’s monster. It is also helpful to have the authors available to chat if you need help or have issues understanding something, though they might be surprised if you’re using their code in a way they didn’t envision and might not be very inclined to provide support to what they consider internal implementation details. So that could be a hit or miss. Luckily the people behind both nsq and bosun were supportive of my endeavors but I also made sure to try to figure out things by myself before bothering them. Another reason why it’s good to pick mature, documented projects.

Part of the original meaning of hacking, extended into open source, is a mindset and practice of seeing how others solve a problem, discussion and building on top of it. We’ve gotten used to - and fairly good at - doing this on a project and library level but forgot about it on the level of code, [code patterns] 1 and ideas. I want to see these practices come back to life.

We also apply this at Raintank: not only are we trying to build the best open source monitoring platform by reusing (and often contributing to) existing open source tools and working with different communities, we realize it’s vital to work on a more granular level, get to know the people and practice cross-pollination of ideas and code.

Next stuff I want to read and possibly implement or transplant parts of: dgryski/go-trigram, armon/go-radix, especially as used in the dgryski/carbonmem server to search through Graphite metrics. Other fun stuff by dgryski: an implementation of the ARC caching algorithm and bloom filters. (you might want to get used to reading Wikipedia pages also). And mreiferson/wal, a write ahead log by one of the nsqd authors, which looks like it’ll become the successor of the beloved diskqueue code.

Go forth and transplant.

Also posted on my personal blog