How Booking.com handles millions of metrics per second with Graphite

More than 1.55 million room nights are reserved on the Booking.com platform every day. It’s a staggering amount of traffic, and not surprisingly, the Amsterdam-based travel e-commerce company has a lot of knowledge to share about handling metrics at scale.

At GrafanaCon EU 2018, Booking.com System Administrator Vladimir Smirnov gave a talk about why the company started to use Graphite almost five years ago, and how he and his team scaled it to handle millions of metrics per second. “According to the graphiteapp.org, Graphite does three things really well: It kicks ass, chews bubblegum,” he quipped, “and it makes it easy to store and graph metrics.” The ease of use, via an HTTP API, and its modularity were big draws for Booking.com.

The most common use cases for Graphite within the organization were capacity planning and troubleshooting. “For capacity planning, we really need to store data for quite some time, ideally forever,” he said. “Also, we wanted to use it as source of data for troubleshooting and postmortems. We decided to store and visualize the business metrics, so whatever developers think is needed about the application, they also send it there.”

The challenges of Graphite at scale

Over the years, Booking.com’s Graphite grew to consist of hundreds of servers. “It’s hundreds of terabytes of data, hundreds of millions of unique metrics,” Smirnov said. “It ingests more than 10 million unique points per second, and we have tens of thousands of requests per second on both frontend and on backend of the stack that’s being monitored. All those requests fetch 10 million points every second out of our storages from disk. This does not include the stuff that’s fetched from cache.”

The original stack that was built in 2014 required several data centers with exactly the same setup. “You’ll end up having Graphite web and a bunch of servers or containers or virtual machines that talk to storage servers,” Smirnov said. “You’ll have some sort of load balancer on ingestion flow where servers and devices will send their metrics.”

There were problems inherent to this: “Carbon-relay was really a single point of failure for us,” he said. “The second problem was that for our cases, the backend does not really scale well. The carbon cache used to use really a lot of CPU. We do not like the disk usage patterns. Also, there was no easy way to sync our data if we have some storage failures. For example, one storage dies, and a second one leaves, then the second one comes back, and users keep getting the different results every time they refresh, depending on who wants it first. So the render request was really slow for us.”

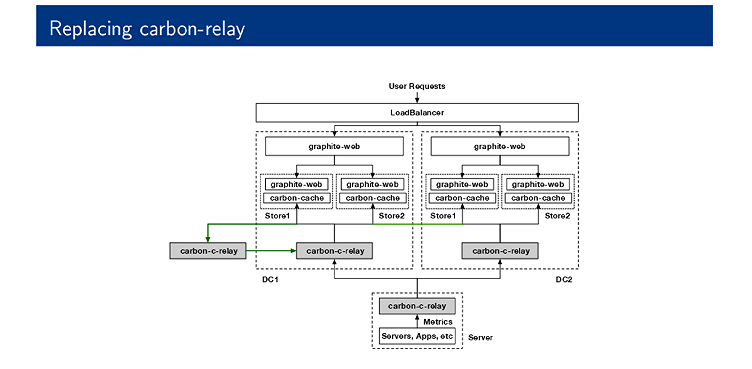

Rewriting the relay

To solve the problem of having a single point of failure, a Graphite team at Booking.com rewrote the relay in C. “We decided to place a relay as close as possible to the producers of metrics, so every server has a small relay that knows about several bigger endpoints—basically several relays in each data center,” he said. The central relay knows about the storages and how to balance the metrics, and has rules to get rid of some things or to rewrite them into something else.

The relay provides redundancy and speed. “It can consume more than a million data points per second using only two CPU cores, which was, well, a really desirable feature for us at that moment,” Smirnov said.

Using the Graphite line protocol, the relay reads metrics, validates them, and decides where to send them. Importantly, it can buffer the data for some time if there’s a network or node failure, and there is no data loss in most cases of outages.

But the company’s Graphite journey didn’t end there. “The more metrics we got, the more strange stuff we started to notice,” Smirnov said. “First of all, we saw that the metric distribution was not quite good with the bulk stream consistent hashing algorithm. In the worst cases, the difference was about 20%, so basically when one server ran out of disk space or ran out of capacity, other servers were fine.”

The team found a white paper from Google about the jump hashing algorithm, and implemented it in the relay to achieve an almost even distribution. The difference with the new algorithm was less than 1%.

More recently, they realized that this implementation wasn’t easy to maintain, so they started to rewrite the relay in Go. They also tried to switch from the traditional plaintext carbon protocol input and output to start using Kafka.

Dealing with differences between metrics

In the original 2014 stack, “when one server dies, and it comes up after a while, people will start seeing a difference.” He added, “Every time they refresh the graph they will see a different result because, well, two servers got a different amount of data.”

Their approach to solve this problem was simple: They wrote a small proxy that sits in front of the front-ends that emulates the behavior of graphite-web that fetches the data from all known backends that contain this metric. “If there are any gaps inside, it will try to do its best to fill up the gap and present the user the full set of data,” he said. This fix reduced the problems almost to zero. “There are still rare cases when it can happen but, well, almost not noticeable by normal people,” he said.

They also decided to replace the carbon cache, which wasn’t easy to maintain, with an open source project called Go Carbon. “We contributed some code to it to allow to read the metrics and present them in the way the Graphite web was expecting them,” Smirnov said. “That also solved some of the problems with the speed of the queries, because in our test, the Graphite web query carbon cache allowed us to do something like 80 requests per second, and after rewriting the stuff in Go, it was almost 3,000 requests per second, per backend.”

Enabling Grafana

Smirnov’s team installed Grafana, and “people really liked it because it’s so much nicer than Graphite web,” said Smirnov. “By using it, they started to do more and more complex queries, more complex dashboards, and that again became a problem from the perspective of speed and other stuff.” They decided to write some parts of the Graphite web in Go. “That led to a quite significant decrease of the average response time from the front-ends,” he reports. “Basically, this was the moment when we rolled out Carbon API as a main data source for Grafana. Average response time reduced from something like 15 seconds to less than one.”

All the work that Booking.com did on functions and parsing features is available as a Go library.

Improving the backend

One resilient and failure-safe approach to storing data for a backend is Replication Factor 2. However, the backend tools the team was using to do the operational work on Graphite didn’t work with Replication Factor 2. They experimented with using Replication Factor 1, sending it twice to split the server fleet manually into two equal parts and sending it out to different parts.

In order to choose which approach to use, they created a replication factor test to calculate the potential for data loss in case of server failure. For a group of eight servers, the team found that with Replication Factor 2, you lose a smaller amount of data than with Replication Factor 1. But when two servers fail with Replication Factor 2, there will always be a small percentage of data that is definitely not available. With Replication Factor 1, the probability that data is lost when two servers fail is only 15%. The team opted for using Replication Factor 1 in two different sets of servers to reduce the probability of losing data.

More issues to resolve

With hundreds of servers and people, Booking.com has some particular challenges. “Sometimes you get something like, alert: disk space usage is showing you have 10% left, please provide new servers,” said Smirnov. “But the problem is that, well, you checked it five minutes ago, and it was like 20% left, so who the hell created all this new strange stuff?”

The truth is, “Because it’s really easy to send data to Graphite, it’s really easy to abuse it,” Smirnov said. “For example, instead of the variable name you can by accident get the address of the variable and send it instead. Every instance of your application will create a bunch of strangely named metrics. You never know until you actually encounter something like that.”

To find a solution, the team began collecting all possible stats about the backend, all the meta information about the file: when was it last accessed, when was it created, what’s the size. Using a library found on Github, the team presented the disk space in flame graphs.

“When you have something that can be considered as a good data point, it’s really easy to switch to the next one and see the difference, so that you can easily spot where it happened, and tell if a metric is a legit one or if someone created it by accident,” said Smirnov. “This also allowed us to do a lot of analytical queries across all the data set: how people use our stack, what metrics are the most commonly requested, and so on. Around 99% of metrics nobody cares about, but the last 1% is something really hot, and we can do some optimizations based on that, for example.”

What’s next

The team has a substantial to-do list to keep improving Booking.com’s Graphite stack.

- Find a replacement for whisper because it doesn’t have any compression. “It’s 12 bytes per point, so it takes really a lot of disk space, and most of our vacants are actually disk space bounded, not CPU, memory or network bound.”

- Replace the Graphite line protocol between the components. “We are looking forward to migrating to streaming gRPC, but in terms of ingestion it’s still line protocol across all the stack. After the first step you don’t really need it. You can use something that’s compressed and even binary not to spend the CPU time on the backends.”

- Make the flame graphs more or less production ready for other use cases, perhaps even having something like differential flame graphs.

- Start collecting the stack traces from the Graphite stack in production to get some insights about what’s happening under the hood when we face problems.

TL/DR

While the team considers the Graphite stack still a work in progress, Smirnov can recommend the basic setup that they have come to after five years of experimenting and troubleshooting. “It was really surprising for us that not only we use our stack, but some part of our stack is used by eBay Classified and Slack,” he said.

To sum up: “Every frontend has exactly three pieces of software - Grafana, Carbon API, and Carbon Zipper (which is included in Carbon API)—and whenever the frontend has a problem, we just deploy a new server that contains these three pieces,” said Smirnov. “For the backend side, it’s always Go Carbon with carbonserver enabled inside. It’s always a single process, and whenever we run out of disk space or like in rare cases when we hit the limits in terms of capacity, like amount of metrics per second we can receive from the storage side, we deploy a bunch of new servers and do the rebalancing with buckytools.”

Smirnov, who has now left Booking.com, maintains the original Carbon API project that he started working on when he was there. Booking’s current stack can be found at its GitHub account. For more details, check out the slides from his presentation.